Audio File Formats and Audio Quality

Once analog audio is converted to digital by an ADC, we often want to store it to play back later. There’s two things we need to know about our ADC in order to make use of the audio: the sample rate, and bit depth. When storing digital audio, we usually like to store this “metadata” along with the raw sample data itself. (We might also be interested in other information, like when it was recorded, how many channels were recorded and so on. All that info is considered part of the metadata as well.)

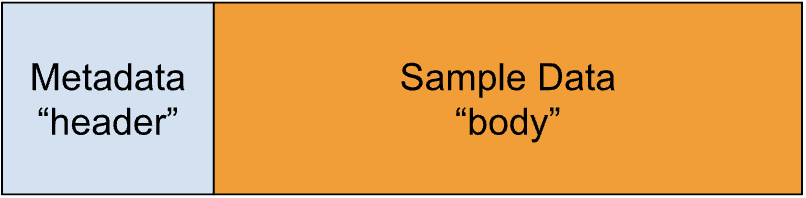

Ideally, we’d like to store the sample data and metadata in a single file, so it can be easily moved around in one piece. Many file formats put the metadata at the beginning of the file, often in a “header” (See Fig 1), and the rest of the file is often filled with the raw sample data, so this is called the “body”. A variety of file formats exist that follow this general premise, including AIFF, CAF, WAV, RF64 and WAV64. Over the years, other styles have been tried (such as the Sound Designer II format, which split the raw and metadata into two “forks” of a file, a filesystem feature only used on the original Mac OS as far as I know), but the header/body style has stuck.

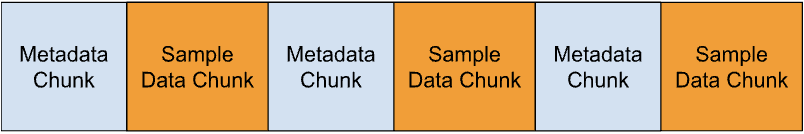

While the header/body model is correct for some formats, it can be an oversimplification for others. It’s more accurate to think of a file in “chunks”, each of which may contain some or all the metadata or the raw sample data, like in Fig 2. In most formats, there are some restrictions about the order of the chunks. eg, you typically must put the sample rate and bit depth before the sample data. Most file formats also start with some sort of “preamble”, which might contain a file type “signature”, such as the four characters AIFF or WAVE, so that the file type can be identified even if the extension is missing or incorrect. It’s possible to skip over chunks that are not understood, so you can write software that can read the file even if it doesn’t understand all the chunks. This allows these formats to be somewhat extensible while still being backwards compatible.

Because all major audio file types store both the raw sample data and information about the format of that data, they can all store the raw audio data in multiple formats. So, for example, the WAVE format supports a variety of bit depths and sample rates. Because there are multiple file types that can handle multiple raw data types, we need to distinguish between the file format (sometimes called the “container” format) and the sample format (sometimes called the “encoding” or “CODEC”).

Container Formats and Encodings

A lot of folks think that some container formats store data more accurately or in some way better than others, and that, therefore, some container formats are better than others, leading to the myth that WAV files sound better than AIFFs (or the also incorrect myth that AIFFs sound better than WAV files). However, the truth is, as long as the encodings are the same, the quality will be identical regardless of the container format. This is because all the data needed to represent the original sequence of numbers is preserved in either case.

Of course, an 8-bit AIFF file will sound worse than a 16 bit WAV file, but that has nothing to do with the limitations of the file format (the container); it has to do with the format of the raw audio (the encoding).

Why are there all these different formats? Historically, different vendors have come up with different ways to store the data, and made choices that suited them. For example, the AIFF format comes from Apple, who wanted a format where the raw number format matched their (at the time) big-endian CPUs, while Microsoft developed the WAV format which matched their little-endian CPUs. Newer formats like CAF, Wav64 and RF64 have come along for a variety of reasons, for example, to support more channels, or larger files sizes or new types of metadata.

Compressed Data Formats

You might be wondering about other containers, like MP3 and M4A, that are popular as consumer formats. MP3 and M4A are container formats, but they have a limited number of encodings they support. Notably, they don’t support raw audio data so they will never preserve audio as accurately as AIFF and WAV. To store data in these containers, it is necessary to compress the audio in an irreversible way, which unfortunately changes the sound quality. Because of the quality loss, these formats are rarely used in audio production (they are also slower to decode and more difficult to seek to arbitrary points, which also makes them bad for music production).

Some formats, like MOV, support a huge range of encodings including both compressed and uncompressed encodings. This flexibility is nice, but it can lead to confusion when your file reader supports some but not all of the encodings, or you are trying to ensure a specific encoding.

As a side note: not all formats have all the raw data in one chunk. The MP3 container, for example, is a pretty unusual format. Because it’s designed for multiple uses – not just storing on a computer – the designers made a different choice about how to structure the format from the typical header/body format described above (Fig 3). In the case of streaming audio, the file might be broken into pieces, so the designers of MP3 decided to break the container into “frames” with the complete metadata of the file duplicated in each frame. Theoretically you can jump in anywhere in the stream and pickup the metadata, without needing the live stream to start over.