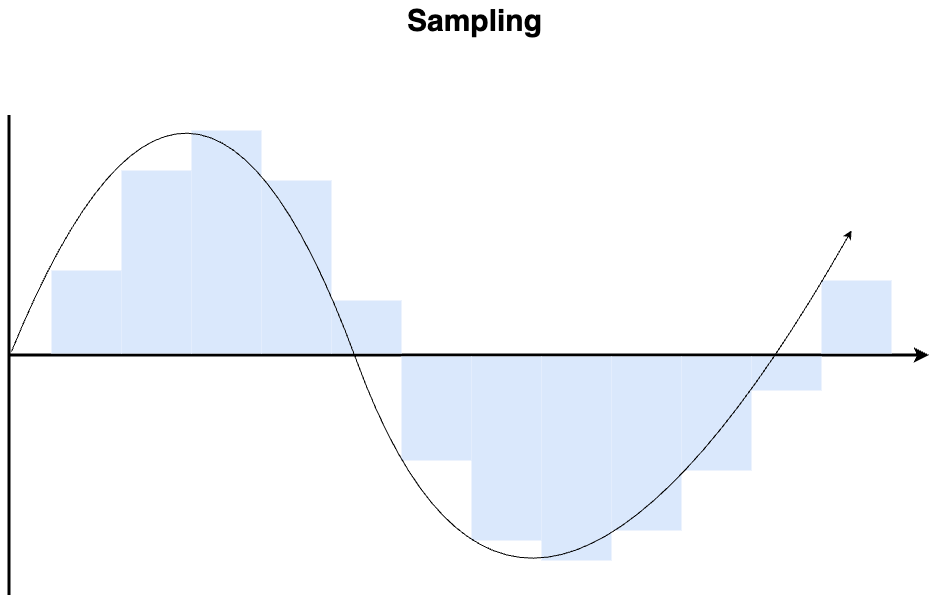

We talked a bit in the last post about how important the sample clock is when converting from analog to digital. It turns out that this sample clock is also critical for digital-to-analog conversion, and understanding clocking is helpful in understanding complex systems with audio, including audio-video synchronization.

Back in college, I helped a friend with his movie by recording and editing audio. When doing audio editing, we took a VCR tape with the edited video that had a special code, called SMPTE Timecode embedded in it. My computer audio workstation had special hardware that would analyze the incoming timecode and figure out exactly what video frame the VCR was playing, so it could playback the audio at the same spot. It worked great — for a few minutes at a time. After a while, the video and audio would drift out of sync, so we couldn’t watch the whole movie from start to finish. This is called “flywheeling” because it relies on the audio and video having the same “momentum” to keep things playing in sync.

The problem with that setup was that the video (coming from the VCR) and audio (coming from the computer) had slightly different internal clocks — one might be a little faster than the other, and over time the difference would compound. (Fancy studios at the time had special signals that both the audio and video equipment would sync to, but we couldn’t afford such stuff).

You might think this wouldn’t be an issue in a single computer playing back both video and audio, but as we learned in our last post, the digital audio sampling clock has some very stringent requirements, and it turns out that modern computers and mobile devices still have different clocks for audio and video, so some work is needed to keep things in sync. Generally the OS or player software handles keeping the audio and video in sync, so we don’t need to worry, but it’s worth understanding how this works.

Generally speaking, the overall technique is to let the audio clock take the lead. This is because it is the highest the most sensitive to fluctuations. Compared to video where a .1% change in playback speed is not noticeable, a .1% change in playback speed in audio can change 1,000 Hz to 1001 Hz, which is quite noticeable in many contexts. For short content, flywheeling works well, and for longer content, the video can be resynched to the audio, without causing any noticeable problems.

There are still times when flywheeling is necessary: for example, apps like TikTok let you play audio and let you record video alongside or record a reaction video along with someone else’s source video. In these cases, flywheeling is the easiest option, but it works fine because the content is usually short.

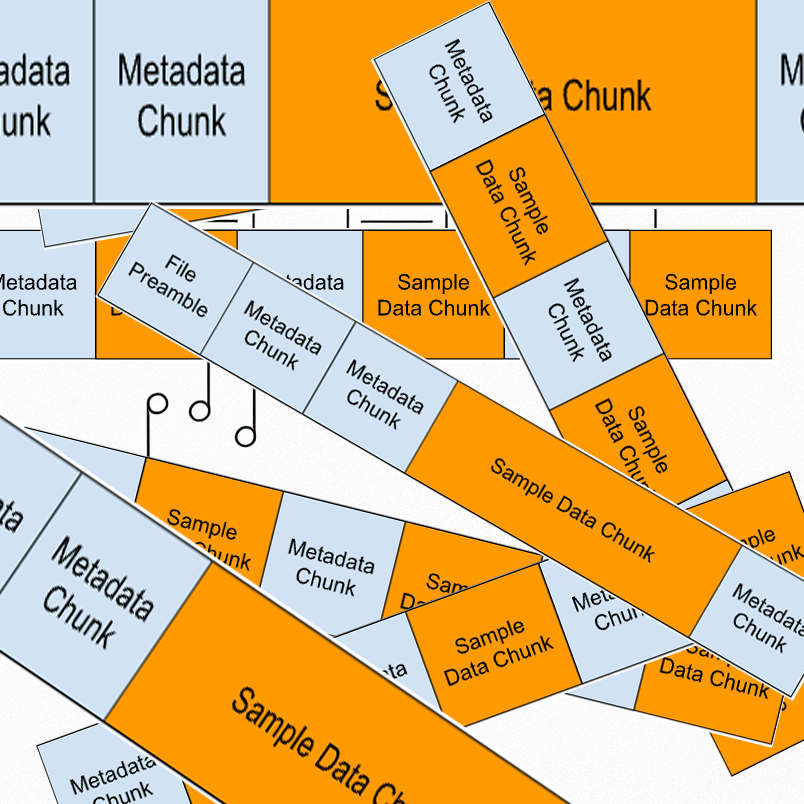

You might wonder how audio and video are synchronized inside a file. File formats that can contain both audio and video, like Quicktime and MP4, don’t have too much to worry about, because, within the file, individual video frames and audio samples have a clear time that they are supposed to play, and a clear speed they are supposed to play at. It is up to the player to make sure they actually play at the right time and speed.

One place things can get out of sync, even in modern life, is in video calls. We’ve all experienced a Zoom or Google Meet call which starts fine but at some point the audio starts to lag. This happens because audio and video are separated into separate streams. This is not a problem in and of itself, as long as they are played at the same rate, but sometimes packets get lost and the player has to decide what to do. The player doesn’t always know what to fill in, or how to buffer, and may repeat or skip parts of the audio and video by different amounts. In this case, timing information in the packets can act like the SMPTE timecode and can, in theory, correct the issue — but reality isn’t always as good as theory. I usually find the best solution is to try reconnecting.